US Pharm.

2008;33(12):20-22.

Visualizing organs of the

gastrointestinal (GI) tract, such as the liver and gallbladder, and detecting

cysts, abscesses, tumors, and obstructions can be achieved through

radiographic imaging.1 Contrast agents, used during a computed

tomography procedure, for example, can illuminate specific hollow structures

and vascularity of the GI tract.1 A coronary angiography, also

known as cardiac catheterization, can detect blockages through radiographic

visualization of coronary vessels subsequent to an injection of radiopaque

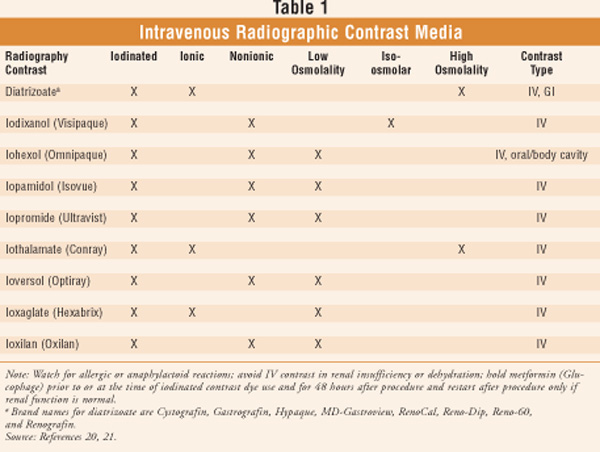

contrast medium (CM).2,3 Iodinated contrast media (TABLE 1),

used for the identification of vascular structures, are relied upon

continually in radiologic and cardiologic procedures.4

Contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN) is an increasingly important complication

associated with the use of iodinated CM.4

Diagnostic imaging procedures

that require intravenous radiographic CM have increased in number and

have resulted in an increase in CIN.5 CIN is considered a common

complication in angiographic procedures.6,7 This is an important

issue for clinicians, including pharmacists who provide services for the

elderly, since among aging individuals there is an increased incidence of

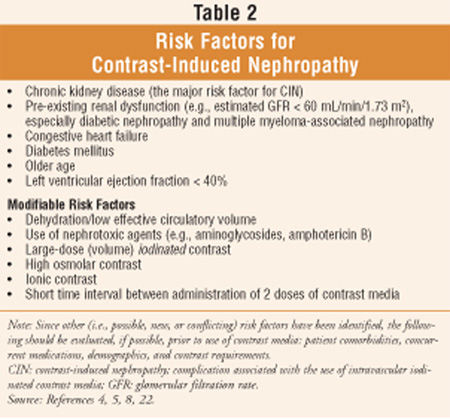

renal impairment and diabetes, two of the risk factors (TABLE 2) for

CIN.8,9 CIN is one of the most serious adverse events associated

with the use of CM and is the third leading cause of hospital-acquired acute

renal failure.10,11 It has been reported that individuals who

develop CIN have increased morbidity, higher rates of mortality, lengthy

hospital stays, and poor long-term outcomes.10 Choosing a

particular CM is dependent upon patient and procedural factors, current

evidence, and guidelines.8 Researchers indicate that chances of

developing CIN can be reduced by employing appropriate prevention strategies.10

Common Definitions of

Contrast-Induced Nephropathy

While the incidence

of CIN has been reported to vary widely, the true incidence of this condition

has been difficult to determine since there is no single definition of CIN.8,12

The most common definition of CIN used in clinical trials is: Increase in

baseline serum creatinine (SCr) of 0.5 mg/dL or 25% increase from baseline at

48 hours post CM usage.8,13 Other definitions include: Increase

in baseline SCr of > 0.5 mg/dL or > 25% within 72 hours post CM usage

excluding alternative reasons and Increase in baseline SCr of† >=

0.3 mg/dL, or an increase in SCr 50%, or oliguria (< 0.5 mL/kg/hour for > 6

hours).8,14,15 When CIN is suspected, other causes of renal

insufficiency should be considered in the differential diagnosis, such as

dehydration, interstitial nephritis, and cholesterol embolism.8

Pathophysiology

While changes in

the function of the aging kidney are highly variable and not always

inevitable, a decline in glomerular filtration rate (GFR)is masked in seniors

since a proportional decline in muscle mass renders the serum creatinine to

remain generally constant.16 When this consideration is not

acknowledged, it may result in inappropriate dosing of medications with

associated morbidity.16 Since even a subtle increase in serum

creatinine in seniors can signify a significant decline in renal function,

renal pathology may not be immediately recognized in a geriatric patient.16

The pathophysiology of

nephropathy secondary to contrast media is complex since its development is

multifactorial.8 A recent literature review proposed a simplified

sequence of events: When contrast media is administered in a subject with

impaired renal function (estimated GFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2), an

initial increase in renal blood flow occurs due to vasoconstrictors (e.g.,

endothelin, adenosine); this is followed by a decrease in blood flow, which

allows the contrast media to be pointedly nephrotoxic.8,13,17

Additionally, with the compromise of nitric oxide (a protective vasodilator)

production and the potential release of reactive oxygen species, further renal

injury may ensue.8,17-19 Research continues to identify patients at

risk for and measures to prevent CIN.8

Factors Increasing Risk

In an attempt to

reduce the chance of CIN, risk factors (TABLE 2) should be identified.

Among others, they include chronic kidney disease, older age, dehydration,

diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, and use of concurrent nephrotoxic

medication (including aminoglycosides and amphotericin B).5,10

CM Drug Interaction with

Metformin

Contrast agents may

increase the risk of metformin-induced lactic acidosis. Additionally, due to

the potential for acute alteration in renal function, metformin should be

temporarily discontinued for 48 hours in patients undergoing radiologic

studies involving IV administration of iodinated contrast media.20 Glucophage

should be restarted after the procedure only if renal function is normal.21

Measures for Prevention of

CIN

Currently, there is

no effective treatment for CIN.12 Researchers have noted that

although risk factors for CIN have been identified, an effective prophylaxis

strategy has not been developed for CIN due to a poor understanding of the

pathophysiology and the clinical significance of this condition.22

Among the categories of

developed strategies for the prevention of CIN (i.e., volume expansion before,

during, and after contrast media administration; pharmacological strategies to

prevent reduction of renal perfusion, reduction of tubular flow, and direct

tubular toxicity; renal replacement therapy; and selection of contrast media),

volume expansion is the most critical measure for reducing CIN and should be

used in all individuals undergoing procedures requiring CM.12

Research has revealed a general consensus that hydration protocols implemented

before and after imaging with CM may prevent CIN.9 Unfortunately,

definitive and convincing data have not established amounts to be infused,

infusion timing, and type of solutions (i.e., half-isotonic, isotonic saline

solution, or bicarbonate).9 An extensive Medline search indicates

it is believed that prevention is actually achieved through the correction of

hypovolemia, dehydration, or both.9 In addition to the utilization

of hydration, use of low volumes of iso-osmolar or low-osmolar contrast in

those patients at risk of developing CIN has been recommended.6,22

While the use of

N-acetylcysteine or ascorbic acid has been suggested as possibly valuable in

very high-risk patients, no consensus exists to date regarding the efficacy of

N-acetylcysteine for CIN prevention.8,22 Randomized trials have

provided evidence that interventions such as theophylline, bicarbonate, and

ascorbic acid were appropriate in the emergency department setting and did

decrease the risk of CIN.11

The recommendation to obtain

serum creatinine levels prior to the procedure among patients with renal

disease, diabetes, proteinuria, hypertension, gout, or congestive heart

failure is supported by practice guidelines.22 While beyond the

scope of this article, a list of organizational guidelines and recommendations

regarding the prevention and monitoring of CIN, including the American College

of Radiology and two consensus panels, can be found in Reference 8.

Researchers have called for future research to focus on correctly identifying

higher risk patients and studying therapies as part of large, well-designed

clinical trials.7,22

Conclusion

The wide use of

diagnostic imaging with IV iodinated CM places an ever increasing number of

patients in contact with a renally toxic agent with potential for adverse

outcomes, especially those at risk, such as geriatric patients. CIN is

associated with significant economic and clinical consequences, including

prolonged hospitalization and a higher rate of mortality. While it is believed

that prevention is actually achieved through the correction of hypovolemia,

dehydration, or both, further research involving large clinical trials is

warranted to test and develop prevention protocols.

REFERENCES

1. Chisholm MA,

Jackson MW. Evaluation of the gastrointestinal tract. In: DiPiro JT, Talbert

RL, Yee GC, et al, eds. Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach.

6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, Inc; 2005:605-612.

2. Talbert RL.

Cardiovascular testing. In: DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, et al, eds. Pharmacotherapy:

A Pathophysiologic Approach. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, Inc;

2005:149-170.

3. Beers MH, Jones TV,

Berkwits M, et al, eds. The Merck Manual of Health & Aging.

Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck Research Laboratories; 2004:104-123.

4. McCullough PA. CIN

Consensus Working Panel: Executive Summary.

www.c2i2.org/vol_v_issue_1/cin_consensus_working_panel.asp.

Accessed November 11,

2008.

5. van den Berk G,

Tonino S, de Fijter C, et al. Bench-to-bedside review: preventive measures for

contrast-induced nephropathy in critically ill patients. Crit Care.

2005;9:361-370. Epub 2005 Jan 7.

6. Pannu N, Tonelli M.

Strategies to reduce the risk of contrast nephropathy: an evidence-based

approach. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2006;15:285-290.

7. Zagler A, Azadpour

M, Mercado C, et al. N-acetylcysteine and contrast-induced nephropathy: a

meta-analysis of 13 randomized trials. Am Heart J. 2006;151:140-145.

8. Contrast Media

Reactions Pose Serious Risk of Nephropathy. Medscape Pharmacists. 2008.

www.medscape.com/viewarticle/577203?src=mp&spon=30&uac=7376SZ.

Accessed November 5, 2008.

9. Meschi M, Detrenis

S, Musini S, et al. Facts and fallacies concerning the prevention of contrast

medium-induced nephropathy. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:2060-2068.

10. Stacul F. Reducing

the risks for contrast-induced nephropathy. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol.

2005;28(suppl 2):S12-S18.

11. Sinert R, Doty CI.

Evidence-based emergency medicine review. Prevention of contrast-induced

nephropathy in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med.

2007;50:335-345, 345.e1-2. Epub 2007 May 21.

12. Feldkamp T, Kribben

A. Contrast media induced nephropathy: definition, incidence, outcome,

pathophysiology, risk factors and prevention. Minerva Med.

2008;99:177-196.

13. McCullough PA.

Contrast-induced acute kidney injury. J Am Coll Cardiol.

2008;51:1419-1428.

14. Thomsen HS, Morcos

SK. Contrast media and the kidney: European Society of Urogenital Radiology

(ESUR) guidelines. Br J Radiol. 2003;76:513-518.

15. Mehta RL, Kellum

JA, Shah SV, et al. Acute Kidney Injury Network: report of an initiative to

improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2007;11:R31.

16. Bailey JL, Sands

JM. Renal disease. In: Hazzard WR, Blass JP, Halter JB, et al, eds. Principles

of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill,

Inc; 2003:551-568.

17. Bartorelli AL,

Marenzi G. Contrast-induced nephropathy. J Interv Cardiol.

2008;21:74-85.

18. Tumlin J, Stacul F,

Adam A, et al. Pathophysiology of contrast-induced nephropathy. Am J

Cardiol. 2006;98:14K-20K.

19. Persson PB, Tepel

M. Contrast medium-induced nephropathy: the pathophysiology. Kidney Int.

2006;69:S8-S10.

20. Semla TP, Beizer

JL, Higbee MD. Geriatric Dosage Handbook. 12th ed. Hudson, OH:

Lexi-Comp, Inc; 2007.

21. Radiography

contrast. Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopeia. Redlands, CA: Tarascon

Publishing; 2008:53.

22. Pannu N, Wiebe N,

Tonelli M; Alberta Kidney Disease Network. Prophylaxis strategies for

contrast-induced nephropathy. JAMA. 2006;295:2765-2779.

To comment on this article, contact

rdavidson@jobson.com.