US

Pharm.

2006;1:HS-14-HS-22.

Fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) is

a chronic, soft-tissue pain disorder that affects about 3.7 million people in

United States, the majority (75%) of whom are women.1 The condition

is characterized by fatigue and widespread pain in muscles, ligaments, and

tendons and is a common cause of chronic musculoskeletal pain. Patients with

FMS often report tender point pain that occurs in local sites --usually in the

neck and shoulders--and radiates out into other regions of the body. Such pain

can occur in areas where the muscles attach to bone or ligaments, but the

joints are not affected. Pain resulting from FMS is similar to that of

arthritis and has been described as stiffness, burning, radiating, and aching.

The generalized pain of FMS is often

accompanied by many other symptoms, including depression, headache,

paresthesias, fatigue, poor sleep, and morning stiffness (Table 1). As more

attention is given to the pharmacological treatment of this disorder,

pharmacists will likely receive questions from patients with FMS. This article

will help pharmacists to effectively counsel patients with fibromyalgia and

recognize patients with FMS-like symptoms who are self-treating, since some of

these patients may need medical treatment.

Epidemiology

The exact etiology and

pathogenesis of FMS is essentially unknown. Due to its similarity to other

disease states and lack of objective symptoms, the disorder is often difficult

to diagnose. FMS affects about 2% to 3% of the general population and more

than 5% of patients in general medical practice.1,2 The typical age

of patients with FMS ranges from mid-30s to late-50s. One study found that

generalized musculoskeletal pain in women was increasingly prevalent as age

increased from 18 to 70 years.3 Patients often report that their

pain is continuous and can vary depending on time of day, weather changes,

physical activity, and the presence of stressful situations. Insomnia often

exacerbates the pain.

Pathophysiology

Multiple

physiologic alterations such as sleep disturbances, altered neurotransmitter

metabolism, and muscle structure abnormalities have been proposed to account

for the symptoms associated with FMS. Such theories involving sleep and

neurotransmitter alterations are widely accepted. Poor sleeping patterns are

very prevalent in patients with FMS and can affect their stress response

system. This contributes to negative mood, cognitive difficulties, and

increased pain perception.4-6 The stress response may become

maladaptive in chronic pain syndromes and contribute to symptoms such as

fatigue, poor sleep, low mood and/or anxiety, and "flu-like" illness.

4 Evidence suggests that psychological stress can initiate alterations

of the stress response system, with multiple adverse effects on the

neuroendocrine, immunologic, and autonomic nervous systems.5,6

Decreases in serum serotonin, which modulates pain and stage 4 sleep, have

also been noted. In addition, levels of serotonin's precursor, tryptophan, may

be low in patients with FMS.5 The theory that altered serotonin may

be involved in the pathogenesis of FMS has led to the use of selective

serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for treatment. Other biochemical

abnormalities include an elevated level of substance P in cerebral spinal

fluid (80% of patients).7 Hyaluronic acid levels are high early in

the day, and changes in serum levels are related to the intensity of morning

stiffness.7

The simultaneous processing of

sensory and emotional aspects of pain may influence the subjective intensity

of FMS symptoms. Patients with FMS have distorted central nociceptive

processing, which alters the pain perception and pain tolerance thresholds.

The two principal effectors of the stress response, the hypothalamic pituitary

axis and the sympathetic nervous system, are activated in pain states.6

Negative emotions and psychological factors can heighten the pain experience

and pain-processing systems. The four principal categories of pain are (1)

nociceptive pain (matches the noxious stimulus), (2) neuropathic pain (may

follow injuries/diseases that directly affect the nervous system), (3)

psychogenic pain (occurs in disorders associated with psychological factors),

and (4) complex pain of complex etiology (occurs in fibromyalgia). The number

of painful tender points is strongly correlated with psychological distress in

patients with FMS (table 2).

Aggravating Factors in FMS

Fibromyalgia is a

chronic illness whose outcomes are influenced by the interaction of

biological, psychological, and sociological factors.8 Important

biological factors include gender, sleep, physical condition, neuroendocrine

and autonomic dysregulation, and sensitization to pain. Female gender is

associated with increased pain sensitivity. Clinical studies have shown that

females have more pain, use analgesics more often, and are influenced by

fluctuations in hormone levels.9 Stress and noxious stimuli are

more likely to trigger a response in females than in males. Compared with men,

women report more symptoms, including unexplained symptoms.9,10

Other variables such as environment and ethnicity can influence the course of

pain and fatigue. Cognitive factors in the pain and fatigue associated with

FMS include hypervigilance, management strategies, perceived pain control,

mood, depression, anxiety, and personal behaviors. Psychosocial factors such

as poor health of parents, poor family environment, and childhood

abuse--particularly sexual abuse--may influence a patient's vulnerability or

susceptibility to FMS. The disorder often has a high impact on the patient,

the patient's family, and society. Physical functioning, emotional well-being,

social functioning, and general health perception all contribute to the

patient's quality of life. In approximately one half of cases, symptoms of FMS

appeared to begin after a specific event, most often some form of physical or

emotional trauma.11

Typical Clinical

Presentation of FMS

The chief complaint

of patients with FMS is diffuse musculoskeletal pain. Several characteristics

and painful "trigger points" are associated with FMS (tables 1, 2

). Although initially the pain may be localized, it can spread to many muscle

groups. Patients typically complain of pain in the neck, back, chest wall,

arms, and legs. The pain is recurring and fluctuates in intensity. Sensations

of tingling and burning are often described. Patients with FMS may have a

variety of symptoms that are not well understood, including abdominal pain

suggestive of irritable bowel syndrome and bladder symptoms indicative of

interstitial cystitis. Fatigue is one of the most common complaints. Most

patients report light sleep and/or feeling groggy in the morning. Mood

disturbances, short-term memory loss, headaches, and feeling faint and/or

dizzy are also frequent complaints. Less common symptoms include ocular

dryness, dysphagia, palpitations, dyspnea, dysmenorrhea, osteoporosis, weight

fluctuations, allergic symptoms, and night sweats. Typically, the only helpful

finding on physical exam is excessive tenderness. The rest of the exam is

usually only helpful to rule out other conditions. Patients often have

difficulty distinguishing joint and muscle pain and may complain of swelling,

although the joints do not appear inflamed on exam. There is no evidence to

indicate a connective tissue disorder unless the patient has an associated

illness. FMS may occur with any rheumatic disorder.12

FMS frequently exists with

other illness. In one study, 22% of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus

met the American College of Rheumatology criteria for fibromyalgia.10

Coexisting connective tissue diseases, psychiatric illnesses, sleep

disorders, and chronic infections complicate the assessment and diagnosis of

FMS because of the similarities in symptoms. Approximately 30% of patients

with FMS have major mood disorders.13 A change in affect is often

the patient's primary complaint.14 The combination of poor

sleep, fatigue, and widespread pain is observed in disorders such as restless

legs syndrome and sleep apnea. Pain and tenderness are also present in some

patients who have an infectious disease. FMS overlaps with other poorly

understood syndromes. Patients with chronic fatigue syndrome often meet tender

point criteria for FMS. Myofascial pain can also complicate assessment and

diagnosis. Patients with chronic fatigue syndrome often complain of localized

pain, and some consider it to be a localized form of FMS.15

Overview of Treatment of FMS

The classification

and diagnosis of FMS is a critical step in improving a patient's quality of

life. The goal of FMS therapy is palliation of symptoms, since there is no

curative treatment of FMS and remission of all symptoms is rarely achieved.

Since there is no consensus on effective pharmacological treatment for FMS,

most patients are treated symptomatically for pain, insomnia, underlying

depression, and muscle tension.

Treatment is multifaceted and includes

patient education, pharmacotherapy, physical and occupational therapy, and

occasionally behavioral or psychotherapy. A treatment program that

incorporates physicians, rehabilitation, and mental health specialists will

likely be more successful than drug treatment alone.16 Results of

educational interventions alone are often superior to those in control groups,

with respect to pain relief.16 Educational interventions should

explain the nature of FMS and provide a rationale for the treatment program. A

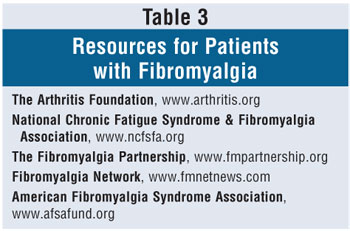

list of resources for patients with FMS can be found in Table 3. Patients

should have an active role in the treatment plan, understand the role of

stress, and learn techniques that can reduce it.

Pharmacotherapy

SSRIs and tricyclic

antidepressants have proven to be somewhat effective. In one study, fluoxetine

was superior to placebo at reducing pain and change in mood.17

Doses of up to 80 mg of fluoxetine per day were used in 60 women (ages 21 to

71 years) with FMS. Patients were randomly assigned to receive fluoxetine (10

to 80 mg/day) or placebo for 12 weeks in a double-blind,

parallel-group, flexible-dose study. Women who received fluoxetine (mean dose,

45 mg/day) had a significant (P = .005) improvement of the Fibromyalgia

Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) total score, compared with women who received

placebo. The FIQ is a self-reported survey of 19 items that measure physical

functioning and intensity of symptoms. The fluoxetine group also showed

significant improvement of their pain (P = .002), fatigue (P =

.05) and depression (P = .01) scores, compared with women who received

placebo. The number of tender points and total myalgic scores improved more in

the fluoxetine group than in the placebo group, but these differences were not

statistically significant. Fluoxetine was generally well tolerated.

A meta-analysis of clinical

trials using antidepressants for the treatment of FMS shows that these drugs

have only modest efficacy in treating many of the symptoms of fibromyalgia.

18 Sixteen randomized placebo-controlled trials were identified, of

which 13 were appropriate for data extraction. There were three classes of

antidepressants evaluated: tricyclics (nine trials), SSRIs (three trials), and

S-adenosylmethionine (two trials). Patients were more than four times as

likely to report overall improvement and reported moderate reductions in

individual symptoms, particularly pain. It is uncertain whether this effect is

independent of depression. Doses lower than those required for depression

should be used at bedtime (e.g., nortriptyline 25 to 50 mg at bedtime).

However, the adverse side effects of some of these drugs may limit their use,

especially the highly anticholinergic drug amitriptyline.

A number of medications,

including analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and central nervous system (CNS) drugs

have been used in the treatment of FMS. In 2003, a study assessed the efficacy

of acetaminophen and tramadol in patients with fibromyalgia.19 The

purpose of the study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a combination

analgesic tablet (37.5 mg tramadol/325 mg acetaminophen) for the treatment of

fibromyalgia pain. The 91-day, multicenter, double-blind, randomized,

placebo-controlled study compared tramadol/acetaminophen combination tablets

with placebo. The primary outcome variable was cumulative time to

discontinuation (Kaplan-Meier analysis). Secondary measures at the end of the

study included pain, pain relief, total tender points, myalgia, health status,

and FIQ scores. There were 315 subjects enrolled in the study, 94% female.

Tramadol/acetaminophen–treated subjects had significantly less pain at the end

of the study, better pain relief, and better FIQ scores (all statistically

significant). Indexes of physical functioning, role-physical, body pain,

health transition, and physical component summary improved significantly in

subjects receiving the tramadol/acetaminophen tablets. Discontinuation due to

adverse events occurred in 19% (n = 29) of tramadol/acetaminophen–treated

subjects and 12% (n = 18) of placebo-treated subjects. Patients who had

experienced treatment failure on other medications were excluded. In addition,

tramadol as a weak mu-receptor agonist has some abuse potential and should be

prescribed with caution.

In a study of 58 females with

fibromyalgia, 74.1% completed an eight-week treatment period testing the

combination of carisoprodol, acetaminophen, and caffeine versus placebo.20

Twenty-three patients received placebo and 20 received active medication. In

the placebo group, 56.5% of patients used additional analgesics, compared to

only 20% in the active treatment group (P = .015). Forty-three percent

of patients in the placebo group and none of the patients in the active

treatment group used tricyclic antidepressants, anxiolytics, or sedatives (P

= .0008). Patients receiving active medication reported statistically

significant improvement for pain (P <.01), sleep quality (P

<.01) and a general feeling of sickness (P <.05). An increased

pressure pain threshold was found in the active treatment group after eight

weeks in 70% of the sites measured, while the pressure pain threshold

increased in only 30% of the sites in the placebo group. The authors concluded

that the combination of carisoprodol, acetaminophen, and caffeine is effective

in the treatment of fibromyalgia. However, the study's small sample size

should be considered.

A randomized crossover trial

studied the use of fluoxetine and amitriptyline together.21 This

combination provided better results than either drug alone. The use of a drug

or combination of drugs that inhibit reuptake of both serotonin and

norepinephrine may be more useful than a drug that targets only one

neurotransmitter. Duloxetine and venlafaxine are two drugs that inhibit

reuptake of both neurotransmitters and may be useful in the treatment of FMS.

Pregabalin is an alpha-2 delta

ligand being studied for chronic pain and epilepsy. A recent trial was

conducted to evaluate the efficacy and safety of pregabalin for treatment of

symptoms associated with FMS.22 The multicenter, double-blind,

eight-week, randomized study measured the effect of pregabalin doses of 150,

300, and 450 mg/day on pain, sleep, fatigue, and health-related quality of

life in patients with FMS (n = 529) against placebo. The primary outcome was

the comparison of mean end-point pain scores, derived from daily diary ratings

of pain intensity from the pregabalin treatment groups and the placebo group.

Pregabalin at 450 mg/day significantly reduced the average severity of pain in

the primary analysis compared with placebo. Significantly more patients

treated with pregabalin had improvement in pain at the end point (29% vs. 13%

in the placebo group; P = .003). Pregabalin at 300 and 450 mg/day was

associated with significant improvements in sleep quality, fatigue, and global

measures of change. Dizziness and somnolence were the most frequently reported

adverse effects. Rates of discontinuation due to adverse events were similar

across all treatment and placebo groups. The authors concluded that pregabalin

at 450 mg/day was well tolerated and effective to treat FMS compared with

placebo, resulting in reduced symptoms of pain, disturbed sleep, and fatigue.

Duloxetine was studied in 207

patients with primary fibromyalgia, with or without current major depressive

disorder.23 The study was a randomized, double-blind,

placebo-controlled trial conducted in 18 outpatient research centers in the

U.S. Subject charcteristics were as follows: 89% female, 87% white, mean age

of 49 years, and 38% with a current major depressive disorder. After a

single-blind placebo treatment for one week, subjects were randomly assigned

to receive duloxetine 60 mg twice a day or placebo for 12 weeks. Compared with

placebo, duloxetine-treated subjects showed significantly greater improvement

of pain, fibromyalgia, and quality of life. Duloxetine treatment improved

fibromyalgia symptoms and severity of pain regardless of baseline status of

depression. Compared with placebo-treated females, duloxetine-treated females

showed greater improvement on most efficacy measures, while duloxetine-treated

male subjects failed to improve significantly. However, it is important to

note that there were far fewer male subjects in the study. In females, the

effect of treatment on pain reduction was independent of the effect on mood or

anxiety. Duloxetine was well tolerated, with adverse effects being similar to

those reported with placebo.

Cyclobenzaprine has been shown

to be mildly effective in a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials.24

The meta-analysis showed that when patients are treated with cyclobenzaprine,

they are three times as likely to report an improvement in pain. Five patients

would need to be treated with the drug in order for one to improve. According

to this analysis, generalized pain improved early on with the drug, but there

was no improvement in fatigue or tender points at any time. Using a variety of

outcome measures, cyclobenzaprine-treated patients were three times as likely

to report overall improvement and moderate reductions in individual symptoms,

particularly sleep. A 5- to 10-mg dose three times daily was used. Patients

should be warned of prominent CNS side effects with cyclobenzaprine, including

dizziness, sedation, and dry mouth.

There are a number of

nonmedicinal options that may be effective for the treatment of fibromyalgia.

FMS patients typically avoid exercise because they believe that their pain

worsens after exercise. Aerobic activities such as biking, swimming, and

running are sometimes successful in attenuating FMS symptoms. In controlled

trials, aerobic exercise was able to decrease the amount of pain reported and

increased the threshold for pain.25,26 Strength training using

weights and elastic bands has been effective in reducing pain and the number

of tender points.26 Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) is

sometimes used by FMS patients. However, evidence to confirm its

effectiveness is limited. It is important that the physician and pharmacist be

aware of all CAM substances the patient is taking, since some may have drug

interactions with prescribed therapy.

Some studies have shown that S

-adenosylmethionine can reduce pain and improve quality of sleep and sense of

well-being, while other studies have shown no benefit.27,28 In

addition, 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP), the precursor to serotonin, has been

shown to have some benefit in FMS patients.29 Oral doses of 5-HTP

100 mg three times daily improved pain severity, quality of sleep, anxiety,

and the number of tender points. Additional options include hypnotherapy,

meditation, and cognitive behavioral therapy.30,31 These options

have shown some usefulness in selected FMS patients.

Pharmacist-to-Patient Counseling

Pharmacists should

reassure patients with FMS that improvement in pain tolerance, sleep, and

fatigue is likely with appropriate comprehensive and multidisciplinary

treatment. However, patients should understand that there is no cure for FMS,

and complete pain relief is often not possible. Pharmacists should emphasize

that active patient participation in the treatment program can help reduce

symptoms and improve quality of life. Patients should be educated about the

possible causes and aggravating factors of FMS.

REFERENCES

1. Wolfe F, Cathey

MA. Prevalence of primary and secondary fibrositis. J Rheumatol.

1983;10(6):965-968.

2. Campbell SM, Clark

S, Tindall EA, et al. Clinical characteristics of fibrositis: a blinded

controlled study of symptoms and tender points. Arthritis Rheum.

1983;26:817-824.

3. Wolfe F, Smythe HA,

Yunus MB, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the

classification of fibromyalgia: Report of the multicenter criteria committee.

Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:160-172.

4. Goldenberg DL.

Fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, and myofascial pain syndrome. Curr

Opin Rheumatol. 1994;6:223-233.

5. Russell IJ.

Neurochemical pathogenesis of fibromyalgia syndrome. J Musculoskel

Pain. 1996;4:61-92.

6. Clauw DJ, Chrousos

GP. Chronic pain and fatigue syndromes: overlapping clinical and

neuroendocrine features and potential pathogenic mechanisms.

Neuroimmunomodulation. 1997;4:134-153.

7. Russell IJ. The

promise of substance P inhibitors in fibromyalgia. Rheum Dis Clin North Am

. 2002;28:329-342.

8. Engel GL. The need

for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science.

1977;196:129-136.

9. Konecna L, Yan MS,

Miller LE, et al. Modulation of IL-6 production during the menstrual cycle in

vivo and in vitro. Brain Behav Immuno. 2000;14:49-61.

10. Middleton GD,

McFarlin JE, Lipsky PE. The prevalence and clinical impact of fibromyalgia in

systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37:1181-1188.

11. Wolfe F, Ross K,

Anderson J, et al. The prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia in the

general population. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:19-28.

12. Wolfe F. When to

diagnose fibromyalgia. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1994;20:485-501.

13. Hudson JI,

Goldenberg DL, Pope HG, et al. Comorbidity of fibromyalgia with medical and

psychiatric disorders. Am J Med. 1992;92:363-367.

14. Giesecke T,

Williams DA, Harris RE, et al. Subgrouping of fibromyalgia patients on the

basis of pressure-pain thresholds and psychological factors. Arthritis Rheum

. 2003;48:2916-2922.

15. Wolfe F, Simons DG,

Fricton J, et al. The fibromyalgia and myofascial pain syndromes: A

preliminary study of tender points and trigger points in persons with

fibromyalgia, myofascial pain syndrome and no disease. J Rheumatol.

1992;19:944-951.

16. Goldenberg DL,

Burckhardt C, Crofford L. Management of fibromyalgia syndrome. JAMA

. 2004;292:2388-2395.

17. Arnold LM, Hess EV,

Hudson JI, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind,

flexible-dose study fluoxetine in the treatment of women with fibromyalgia.

Am J Med. 2002;112:191-197.

18. O'Malley PG, Balden

E, Tomkins G, et al. Treatment of fibromyalgia with antidepressants: a

meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:659-666.

19. Bennett RM, Kamin

M, Karim R, Rosenthal N. Tramadol and acetaminophen combination tablets in the

treatment of fibromyalgia pain: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled

study. Am J Med. 2003;114:537-545.

20. Vaeroy H,

Abrahamsen A, Forre O, Kass E. Treatment of fibromyalgia: a parallel double

blind trial with carisoprodol, paracetamol, and caffeine versus placebo.

Clin Rheumatol. 1989;8:245-250.

21. Goldenberg DL,

Mayskiy M, Mossey CJ, et al. A randomized, double-blind crossover trial of

fluoxetine and amitriptyline in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Arthritis

Rheum. 1996;39:1852-1859.

22. Crofford LJ,

Rowbotham MC, Mease PJ, et al. Pregabalin for the treatment of fibromyalgia

syndrome: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1264-1273.

23. Arnold LM, Lu Y,

Crofford LJ, et al. A double-blind, multicenter trial comparing duloxetine

with placebo in the treatment of fibromyalgia patients with or without major

depressive disorder. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:2974-2984.

24. Tofferi JK, Jackson

JL, O'Malley PG. Treatment of fibromyalgia with cyclobenzaprine: a

meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51:9-13.

25. Busch A, Schachter

CL, Peloso PM, Bombardier C. Exercise for treating fibromyalgia syndrome.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;CD003786.

26. Jones KD,

Burckhardt CS, Clark SR, et al. A randomized controlled trial of muscle

strengthening versus flexibility training in fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol.

2002;29:1041-1048.

27. Tavoni A,

Jeracitano G, Cirigliano G. Evaluation of S-adenosylmethionine in secondary

fibromyalgia: a double-blind study. Clin Exp Rheumatol.1998;16:106-107.

28. Volkmann H,

Norregaard J, Jacobsen S, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover

study of intravenous S-adenosyl-L-methionine in patients with fibromyalgia.

Scand J Rheumatol. 1997;26:206-211.

29. Puttini PS, Caruso

I. Primary fibromyalgia syndrome and 5-hydroxy-L-tryptophan: a 90-day open

study. J Int Med Res. 1992;20:182-189.

30. Haanen HCM,

Hoenderdos HTW, Van Romunde LKJ, et al. Controlled trial of hypnotherapy in

the treatment of refractory fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 1991;18:72-75.

31. Goldenberg DL,

Kaplan KH, Nadeau MG, et al. A controlled study of a stress-reduction,

cognitive-behavioral treatment program in fibromyalgia. J Musculoskel Pain

. 1994;2:53-66.

To comment on this article,

contact

editor@uspharmacist.com.