US Pharm

. 2006;6:HS-26-HS-36.

Urinary tract infection (UTI)--a broad term

used to describe bacterial infection of the urethra, bladder, and kidneys--is a

problem frequently encountered by health care providers today. In addition to

bacteria, viruses and fungi are other infectious agents that colonize the

urinary tract. Traditionally, UTIs are categorized as uncomplicated or

complicated, or by site of infection. Infections may be symptomatic or

asymptomatic. Lower UTIs include urethritis and cystitis, and upper tract

infections include pyelonephritis and renal abscesses. Acute infections are

usually associated with a single pathogen; chronic infections are usually

polymicrobial.

The economic impact of bacterial UTIs is a

major factor affecting health care expenses today. Both outpatient and

inpatient treatment contribute to overall costs. The urinary tract is the most

common site of hospital infection, accounting for more than 40% of nosocomial

infections (estimated to be 600,000 patients per year) reported by acute care

hospitals.1 The vast majority of hospital-acquired infections are

due to indwelling catheters. On average, a hospital-acquired UTI increases

length of stay by one day, resulting in nearly one million extra hospital

days. The economic impact is between $424 million and $451 million annually.

2 UTI accounts for approximately eight million health care provider

visits in the United States. More than 100,000 hospitalizations per year are

due to infections of the urinary tract. Uncomplicated cystitis is by far the

most common outpatient infection, while pyelonephritis accounts for the

majority of inpatient visits.3 Diagnosis of UTIs accounts for an

estimated $6 billion in health care expenditures.4

Epidemiology

Nearly half of all women will

have a UTI once in their lives.5 It has been reported that one

third of women will have had at least one UTI by age 24 years.6

Simple, uncomplicated UTIs are quite common in women ages 20 to 50. The

geriatric community is frequently affected by these infections. Notably, these

infections often do not cause symptoms.7 UTIs are the second most

common type of infection in the geriatric population, accounting for nearly

25% of all infections in the elderly.6 Fifty percent of elderly

women are affected by asymptomatic bacteriuria. In many cases, bladder

catheriterization is a contributing factor; 38% of chronic care residents

require bladder catheterization, a cause for the increasing incidence of UTIs

in the elderly.8

The pediatric population is also affected by

UTIs. Bacteriuria is present in 2.7% of boys and 0.7% of girls.9

Uncircumcised males have a higher incidence of infection. Uncircumcised

infants younger than 6 months have a higher incidence of gram-negative

uropathogens.6 The rate of hospital admission is higher in

uncircumcised boys, since this population has a 12-fold increased UTI risk.

10 A study by Nuutinen and Uhari found that 35% of boys and 32% of girls

who had their first UTI before age 1 contracted a recurrent UTI during the

next three years.11 Other risk factors for exposure in infants are

hospitalization and catheterization. Children between ages 1 and 5 years have

a 4.5% increased incidence of bacteriuria.

Pathophysiologic Considerations

Transitional epithelium

transports urine from the kidneys to an elastic bladder. The bladder stores

large volumes of urine at low pressures.12 The incidence of

cystitis is greater in women, primarily due to the proximity of the urethral

opening to the vagina and perianal area. Risk factors for UTIs in women

include fecal contamination, recent UTI, decreased fluid intake, irregular

emptying, sexual intercourse, diaphragm and/or spermicide use, a symptomatic

partner, pregnancy, menopause, low vaginal pH or dryness of mucosa, neurogenic

bladder, renal disease, urologic anatomic abnormalities, instrumentation,

immunosuppression, hospitalization, nephrolithiasis, and diabetes.5

UTIs are less likely to occur in men under

50 years of age. Unlike female anatomy, the male urethra is separated from the

rectum by several centimeters and is keratinized by squamous epithelium. The

incidence of UTI becomes similar in men and women at age 65, given the

increased proportion of men with benign prostatic hypertrophy.12

Approximately one fifth of men in their 70s have experienced a UTI.13

Other risk factors for men include urologic abnormalities, neurogenic

bladder, instrumentation, anal intercourse, and immunosuppression.5

Immunosuppressed states in males and females

include age, diabetes, multiple sclerosis, HIV, and other chronic illnesses

that may impair the immune system. For the diabetic patient, the risk of UTI

is greater in females than in males. Diabetic patients generally seem to have

a twofold to fourfold increased incidence of bacteriuria,13 leading

to a higher incidence of pyelonephritis.

Symptoms of UTI are similar among the sexes:

Dysuria (painful urination), urgency, hesitancy, polyuria, and incomplete

voiding may all be associated with acute cystitis. Urinary incontinence,

hematuria, and suprapubic or low back pain may also be present. Typically,

females with acute dysuria have one of three types of infections: acute

cystitis; acute urethritis due to Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria

gonorrheae, or herpes simplex virus; or vaginitis due to Candida or

Trichomonas.

Symptoms that indicate pyelonephritis

include fever, costovertebral angle pain, nausea, and vomiting. Hematuria may

occur in any UTI, but it is more suggestive of nephrolithiasis when

accompanied by flank pain.

In the pediatric population during the first

8 to 12 weeks of life, UTI may be associated with bacteremia. Symptoms in

infants up to 2 years old may include difficulty with feeding, nausea and

vomiting, or failure to thrive. Children ages 2 to 5 may demonstrate fever and

abdominal pain. Children under 5 are at risk for renal scarring.14

Children older than 5 may have the same symptomatology as adults. As many as

25% of young children without pyelonephritis have renal bacteriuria.15

As in other age groups, urine culture is the goal standard for diagnosis of

UTI. However, an adequate sterile urine culture is often difficult to obtain

in the pediatric patient. The urinalysis will support the presumptive

diagnosis of UTI. Markers for infection in a urinalysis are the presence of

nitrites, leukocytes esterase, bacteria, or white blood cells.16 An

infant who is evaluated for fever may require lumbar puncture, in addition to

blood cultures, to evaluate UTI with secondary bacteremia.

Diagnosis

The diagnoses for acute

pyelonephritis, cystitis, and asymptomatic bacteriuria are made by the

presence of bacteria in the urine, usually based on a clean midstream urine

sample. There must be a minimum of 105 colony-forming units per

milliliter (cfu/mL) of uropathogens for diagnosis of acute pyelonephritis and

asymptomatic bacteriuria but only 103 cfu/mL for the diagnosis of

cystitis. Up to one third of cystitis cases would be missed if the criterion

for diagnosis were the same as that for upper tract infections.17

Uncomplicated UTI refers to cystitis and

pyelonephritis that occurs in young, healthy, nonpregnant, or ambulatory

postmenopausal women--all of whom have an anatomically and functionally normal

urinary tract. Patients with complicated UTIs are those who have an associated

risk for infection in the urinary tract (e.g., those with neurogenic bladder,

nephrolithiasis, hospital-acquired infection, diabetes, indwelling catheters,

or who are immunosuppressed). Resistant organisms can be seen in either

complicated or uncomplicated UTIs.17

Because UTIs occur in young healthy men

infrequently, there is debate whether to consider these infections complicated

or uncomplicated, given the paucity of studies in this patient group. The

organisms and sensitivity patterns seem to be the same as in women with

uncomplicated cystitis. Empiric treatment for cystitis would utilize the same

antibiotic choices used in women, but three-day regimens are not recommended

because of the lack of supporting data. A pretreatment urine culture should be

obtained in all men with UTI; however, a posttreatment culture is usually not

necessary. Recurrent infections require evaluation for prostatitis, and if

negative, an evaluation for anatomic abnormalities should ensue.17

In practicality, using bacteriuria for the

diagnosis of cystitis can be cumbersome, since urine culture is not performed

in many cases of uncomplicated cystitis. Urine microscopy has a low

sensitivity (40% to 70%) but a high specificity (85% to 95%) for the diagnosis

of UTI. Pyuria is present in most cases of pyelonephritis--estimated to be

about 90%. Presence of pyuria increases the sensitivity (95%) and specifity

(71%) for the diagnosis of acute pyelonephritis. White cell casts always point

to an upper tract infection.18 Urine culture is positive in 90% of

cases of pyelonephritis, and 20% of hospitalized cases have positive blood

cultures. The cultures were obtained prior to antibiotic therapy in these

cases. There is no evidence that positive blood cultures indicate a more

complicated course in immunocompetent individuals.19

Dipstick urinalysis has become the most

frequently used test due to its cost and fast results. Studies have shown that

dipstick urinalysis, in combination with clinician judgment, greatly improves

diagnostic accuracy in the patient with nonspecific symptoms. Urine dipstick

is positive if there is a presence of nitrate and/or if there is a positive

reaction greater than or equal to trace leukocyte esterase.20

Patients should be screened for asymptomatic

bacteriuria in cases of pregnancy or prior to a urologic procedure or surgery.

Urine culture is the method of choice, since the other types of studies lack

the sensitivity and specificity in these cases. During pregnancy, UTIs are

common in the sixth week and peak during weeks 22 to 24. Pregnant women have a

prevalence of asymptomatic bacteriuria of 2% to 7%. If untreated, 20% to 30%

of these women will develop acute pyelonephritis later in pregnancy. When

pyelonephritis occurs late in pregnancy, there is an association with preterm

labor. Treatment has been shown to decrease this risk by 90%. The current

recommendation by the Infectious Diseases Society of America is to obtain a

urine culture at the end of the first trimester, and if positive, to treat the

bacteriuria. Intrauterine growth retardation and neonatal death have also been

linked to asymptomatic bacteriuria. There are no indications for screening

elderly patients in the community or in institutions for asymptomatic

bacteriuria, as treatment has not been shown to benefit these individuals.

21

Imaging

The diagnosis of pyelonephritis

can usually be made by history, physical examination, and laboratory tests.

Imaging may be necessary when the diagnosis is in question, when there are

recurrent infections, or if the patient responds poorly to appropriate

antibiotic therapy after three days. Computed tomography (CT) with intravenous

(IV) contrast is the test of choice when evaluating the urinary tract. The

most common CT finding in pyelonephritis is wedge-shaped lesions of decreased

attenuation with or without swelling. Anatomic abnormalities and perinephric

abscesses can also be seen on contrast-enhanced scans. Renal ultrasound is

also used to evaluate the collecting system and pyelonephritis and may show

ureteral dilation, suggesting obstruction. Although renal ultrasound is

helpful, a CT scan is more sensitive. Magnetic resonance imaging may be used

in patients who are allergic to iodinated contrast.22

Diagnostic studies for UTI in pediatric

patients are important, given the potential long-term sequelae associated with

undiagnosed or recurrent UTIs. Recurrence may be a marker for genitourinary

abnormalities, and imaging is recommended after the first infection with

concomitant fever. Vesicoureteral reflux encompasses a variety of conditions

that represent the most common abnormality observed in infants and young

children. This condition can lead to recurrent UTIs, resulting in secondary

scarring that causes an increased risk of progression to renal disease into

adulthood. Children with poor clinical response to appropriate treatment

should have immediate renal and bladder ultrasound (RBUS) and voiding

cystourethrography (VCUG).23

Treatment

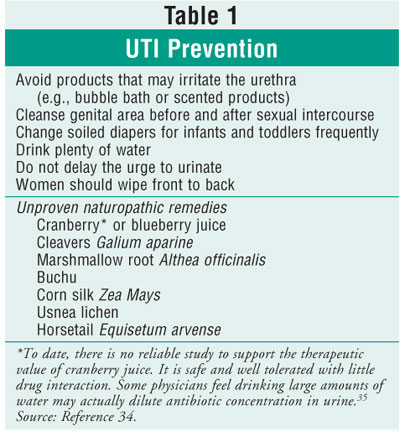

Prevention of UTI is always the

goal of clinicians. There are many proven and unproven strategies to

accomplish this task (see table 1). Most UTIs will clear spontaneously if

untreated, but symptoms may persist for a significantly longer period of time.

Tables 2 and 3 review first-line and alternative treatments for UTI, outlining

the adverse effects of each agent.

In one study, one in 38 women progressed from

uncomplicated cystitis to pyelonephritis without treatment.17 The

most common organisms by far are gram-negative bacilli. Escherichia coli

causes 80% of all community-acquired UTIs among otherwise healthy

individuals, and roughly half of UTIs occur in hospitalized patients and

diabetic patients.2 Other bacteriuria include gram-negative rods

such as Proteus, Klebsiella, and Enterobacter. Antibiotic

resistance has become an important factor to consider in the treatment of

infections. Resistance may occur in ambulatory, institutionalized, and

hospitalized infections. E. coli resistance has been progressing for

more than a decade.24

E. coli Resistance: The resistance

pattern is not uniform in the U.S.; in 2000, it ranged from 10% in the

Northeast to 22% in the West.25 The resistance to

trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) has been significant, and therefore,

it is no longer the first therapeutic choice in complicated UTI or

pyelonephritis. Given the concern of resistance progressing with the

fluoroquinolones, TMP-SMX remains first-line therapy for the most common

uncomplicated cystitis.24 Fluoroquinolones are the primary therapy

for complicated cystitis and acute pyelonephritis. There is still relatively

low resistance to fluoroquinolones for E. coli, but resistance is

significantly emerging with enterococci. Tendonitis and, rarely, Achilles heel

rupture in the geriatric population have been noted with the quinolones.26

Nitrofurantoin is associated with low levels of E. coli resistance,

which is theorized to be due to its multiple mechanisms of action, but the

agent has poor tissue and plasma concentration. Thus, nitrofurantoin has no

use beyond the urinary tract.24 Beta-lactams have significant

problems with resistance--up to 40% in 2002. Fosfomycin is indicated only for

uncomplicated cystitis and has low reported resistance.24

Urinary Catheters:

Any catheterization of the bladder increases the risk of infection, but

indwelling has a higher risk than intermittent catheterization. Treatment of

asymptomatic bacteriuria in patients with chronic indwelling catheters has

shown no benefit.21 When a patient becomes symptomatic, blood and

urine cultures should be obtained prior to treatment. Antibiotics should be

initiated immediately after cultures and should be tailored to the patient,

institution, and susceptibility patterns.

Cystitis:

For uncomplicated cystitis in women, a three-day course of TMP-SMX is

recommended; if the patient is older, a longer course of therapy (seven to 10

days) should be considered. This recommendation applies to areas where E. coli

resistance is less than 20%. Studies have examined three-day courses of

ciprofloxacin versus TMP-SMX, and the results of bacteria eradication were

similar in uncomplicated cystitis. If the patient is allergic to sulfa,

alternative therapies are nitrofurantoin for seven days or single-dose

fosfomycin. Fluoroquinolones are first-line therapy in areas where E. coli

resistance is greater than 20%.27 In pregnant patients with

cystitis, a seven-day duration is preferred for nitrofurantoin or cephalexin.

However, fosfomycin in a single dose is another alternative.27

Women with recurrent bouts of cystitis may need to consider an alternative

form of contraception. Spermicides and diaphragms may predispose women to

infection. Postcoital prophylaxis should be instituted only after the current

infection is treated and a negative urine culture is obtained. Single-dose

TMP-SMX, nitrofurantoin, or fluoroquinolones can be used after intercourse.

18

Complicated Cystitis:

In complicated UTIs, a wide range of bacteria can cause infection.

Fluoroquinolones are effective first-line treatment, given their broad

spectrum of coverage for mild to moderate infections. For more seriously ill,

hospitalized patients, initial empiric therapy includes ampicillin and

gentamicin. Alternative choices of antimicrobials are third-generation

cephalosporins, pipercillin-tazobactam, meropenem, or ciprofloxacin, based on

sensitivities. The expected length of treatment for complicated UTIs is 10 to

14 days. Switching from IV to postoperative coverage largely depends on

clinical improvement. Pseudomonas and Enterococcus are difficult

to treat and may require a longer course of IV antibiotics. Repeat cultures

are recommended one to two weeks after the completion of therapy. If a patient

fails to respond to treatment, repeat cultures should be attained along with

imaging studies to rule out persistent infection secondary to anatomic

abnormalities or stone disease.28

Most complicated UTIs are nosocomial in

origin. The most common pathogens are gram-negative bacteria, which have been

shown to colonize the meatus. Hand washing and good aseptic technique

are imperative in preventing infection. Practitioners must be cautious when

determining the need for indwelling Foley catheters. Intermittent

catheterization reduces the risk of bacteriuria. If a chronic indwelling Foley

catheter is indicated, then the catheter should be changed at least once every

30 days.

Perinephric abscess is considered a

complicated UTI. The most common causative organism is Staphylococcus aureus

. First-line treatment is IV nafcillin or a third-generation cephalosporin.

Vancomycin may be used as an alternative. In most cases, patients will need

surgical intervention or aspiration of the infected fluid collection.29

Acute Pyelonephritis:

Many patients with pyelonephritis need to be hospitalized. (See Table 4 for

indications.) Patients who do not meet absolute indications for

hospitalization are treated successfully in about 90% of cases with outpatient

oral regimens. After the urine culture is obtained, empiric therapy consists

of an oral fluoroquinolone for outpatient treatment. Patients requiring

hospitalization should receive an IV fluoroquinolone or an aminoglycoside

alone or in combination with an extended-spectrum cephalosporin or ampicillin.

Oral treatment may be instituted once the patient is afebrile, clinically

improved, and able to tolerate oral medications and hydration.19

The duration of therapy in pyelonephritis is controversial. In acute,

uncomplicated pyelonephritis, therapy duration ranges from seven to 14 days.

Beta-lactams generally require 10 to 14 days, while the more common

fluoroquinolones or TMP-SMX can require a duration of seven to 10 days.

Complicated pyelonephritis may require a longer course of treatment,

especially if the patients are immunocompromised. Generally, these patients

require 14 to 21 days of therapy or even longer depending on their clinical

course.17

Pediatric Population

Group B streptococcus is the most

common organism seen in neonates. Overall, E. coli is the most typical

organism found in the pediatric population, accounting for 75% to 90% of all

cases. Hospitalized children may require frequent catheterizations, making

Enterococcus and Pseudomonas a possible consideration.30

Management of UTI in the neonatal population

is largely geared toward preventing bacteremia, given the high risk of

meningitis in this age group. Another goal in the treatment of pediatric

patients is prompt diagnosis and empiric treatment to prevent progression of

renal disease and to identify any urinary tract abnormalities.15

Infants and children younger than 5 years of age should be hospitalized if the

clinical suspicion is high for systemic infection. According to the American

Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), hospitalization should also be considered if

noncompliance is a concern, if outpatient treatment has failed, or if the

patient is immunocompromised. A hospitalized patient who remains afebrile for

48 hours and tolerates oral antibiotics may be discharged with continued

therapy on oral antibiotics. Once the infection has cleared, additional tests

may be required to rule out abnormalities of the urinary tract (RBUS and VCUG).

23

The choice of antimicrobial depends on a

number of different factors, such as the patient's clinical status, age (which

may be associated with specific pathogens), and local sensitivity patterns in

the area of practice.15 For neonates with a diagnosis of UTI and

hydronephrosis, amoxicillin is recommended at one third of the normal dosage.

31 Sulfamethoxazole, TMP-SMX, or cephalosporins are beneficial

first-line choices for children who are able to tolerate oral medications.

32 In children who have failed oral therapy, ceftriaxone or gentamicin

administered intramuscularly has been shown to be effective in treating UTI.

23 The AAP recommends seven to 10 days of treatment for uncomplicated

UTIs. For febrile infants with a UTI and children with presumed

pyelonephritis, a 14-day course of therapy is recommended.

Prophylactic antimicrobials may be used in

children with symptomatic UTIs with anatomic abnormalities. There are few data

to support the use of antibiotics in children without anatomic anomalies.

33

References

1. Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention. Guideline for the Prevention of catheter-associated Urinary

Tract Infections. Available at: www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dhqp/gl_catheter_assoc.html.

2. Brown P, Foxman B. Epidemiology of

urinary tract infections transmission and risk factors, incidence and costs.

Infec Dis Clin N Am. 2003;17: 227-241.

3. IDSA Practice Guidelines for

antimicrobial treatment of uncomplicated acute bacterial cystitis and acute

pyelonephritis in women. Available at: www.uptodateonline.com.

4. Stamm WE, Norrby SR. Urinary tract

infections: Disease panorama and challenges. J Infec Dis. 2001;183:S1.

5. Green MB, Bailey PP. Infectious

processes: Urinary tract infections and sexually transmitted diseases. In:

Buttaro TM, Trybulski J, Bailey PP, Sandberg-Cook J, eds. Primary Care: A

Collaborative Practice. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2003.

6. Foxman B. Epidemiology of urinary

tract infections: incidence, morbidity and economic costs. Am J Med.

2002;113:5-13.

7. NCHS: Ambulatory care visits to

physician offices, hospital outpatient departments, and emergency departments:

United States, 1997. Vital and Health Statistics Series 1999:13(143).

8. Warren, JW, Steinberg, L, Hebel,

JR, et al. The prevalence of urinary catheterization in Maryland nursing

homes. Arch Intern Med. 1989:149:1535.

9. Wettergren B, Jodal U, Jonasson G.

Epidemiology of bacteriuria during the first year of life. Acta Paediatr

Scand. 1995;74:925.

10. To T, Agha M, Dick PT, Feldman W.

Cohort sudy on the circumcision of newborn boys and subsequent risk of urinary

tract infection. Lancet. 1998;352:1813-1816.

11. Nuutinen M, Uhari M. Recurrence

and follow-up after urinary tract infection under the age of 1 year.

Pediatric Nephrology. 2001;16:69-72.

12. Hooten TM, Scholes D, Hughes JP,

et al. A prospective study of risk factors from symptomatic urinary tract

infections in young women. N Engl J. Med. 1996;335:468-474.

13. Ronald A, Ludwig E. Urinary tract

infections in adults with diabetes. Int J Antimicrobial Agents.

2001;17:287-292.

14. MacNeily AE. Pediatric urinary

tract infections: current controversies. Canadian J Urol. 2001;8:18-23.

15. Schlager TA. Urinary tract

infections in infants and children. Infec Dis Clin N Am.

2003;17:353-365.

16. Layton KL. Diagnosis and

management of pediatric urinary tract infections. Clin Fam Practice.

2003;5:367-382.

17. Hooten T. The current management

strategies for community-acquired urinary tract infection. Infect Dis Clin

N Am. 2003;17:303-332.

18. Fihn S. Acute uncomplicated

urinary tract infection in women. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:259-266.

19. Ramakrishnan K, Scheid D.

Diagnosis and management of acute pyelonephritis in adults. Am Fam Physician

. 2005;71:933-942.

20. Sultana R, Zalstein S, Cameron P,

Campbell D. Dipstick urinalysis and the accuracy of the clinical diagnosis of

urinary tract infection. J Emerg Med. 2001;20:13-19.

21. Nicolle L. Asymptomatic

bacteriuria: When to screen and when to treat. Infec Dis Clin N Am.

2003;17:367-394.

22. Kawashima A, Leroy A. Radiologic

evaluation of patients with renal infections. Infec Dis Clin N Am.

2003;17:433-456.

23. Shortliffe L, McCue J. Urinary

tract infection at age extremes: pediatrics and geriatrics. Am J Med.

2002;133:55-65.

24. Gupta K. Emerging antibiotic

resistance in urinary tract pathogens. Infec Dis Clin N Am.

2003;17:243-259.

25. Gupta K, Sahm DF, et al.

Antimicrobial resistance among uropathogens that cause community acquired

urinary tract infections in women: a nationwide analysis. Clin Infec Dis

. 2001;33:89.

26. Gold L, Igra H.

Levofloxacin-induced tendon rupture: A case report and review of the

literature. J Am Board Fam Practice 2003;16:458-460.

27. Mehnert-Kay S. Diagnosis and

management of uncomplicated urinary tract infections. Am Fam Physician.

2005;72:451-456.

28. Stamm WE, Hooton TM. Management

of urinary tract infections in adults. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1328-1334.

29. Sanford Guide for Microbiology;

Perinephric Abscess, 2005:22-23.

30. Elder JS. Urinary tract

infections. In: Behrman RE, Kliegman FM, Jenson HB, eds. Nelson Textbook of

Pediatrics. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders; 2000:1624-1625.

31. Caldemone A. Antibiotic

prophylaxis for infants with congenital hydronephrosis [letter]. Pediatric

Infec Dis J. 1999;18:398-399.

32. American Academy of Pediatrics.

Subcommittee on Urinary Tract Infection. Practice parameter: diagnosis,

treatment, and evaluation of urinary tract infection in infants and young

children. Pediatrics. 1999;103:843-852.

33. Dagan R, Phillip M, Watemberg NM,

et al. Outpatient treatment of serious community-acquired pediatric infections

using once daily intramuscular ceftriaxone. Pediatric Infec Dis J.

1987;6:1080-1084.

34. UrologyHealthChannel. Available:

www.urologychannel.com/uti/alternativetreatment.shtml.

35. Lynch D. Cranberry for prevention

of urinary tract infections. Am Fam Physician. 2004;70:2175-2177.

To comment on this article, contact

editor@uspharmacist.com.