US Pharm.

2007;32(10):61-63.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus is a chronic and

progressive syndrome characterized by several metabolic factors that

eventually lead to hyperglycemia. The development and progression to type 2

diabetes significantly increases morbidity and mortality, most often due to

chronic complications.1 In the United States, type 2 diabetes has

reached epidemic proportions. In 2005, approximately 21 million adult

Americans had diabetes, and it was estimated that an additional 1.5 million

new cases would be diagnosed that same year.2 The prevalence of

diabetes is only expected to rise. The financial impact of this disease state

is staggering, with an estimated $132 billion directed toward the total cost

of care in 2002.3 This article highlights major risk factors that

are commonly associated with type 2 diabetes.

The development of diabetes tends to be

insidious. The presence of risk factors may precede the actual onset of the

disease by several years. Many times, patients may have diabetes for several

years before symptoms are apparent or a diagnosis is made. In some cases,

patients have identifiable risk factors for the disease that are not addressed

in a medical setting, or risk factors are addressed but not aggressively

enough. Decreasing the risk of progression to diabetes may greatly lower the

development of complications such as cardiovascular disease, retinopathy,

nephropathy, and neuropathy. Pharmacists have the ability and obligation to

educate patients and be further involved in their care when appropriate.

Identifying risk factors to aid primary prevention is an important

intervention needed to decrease the associated morbidity and mortality.

Prediabetes

Prediabetes

refers to blood glucose impairment that is not yet classified as type 2

diabetes. Without intervention, the risk of progression to overt diabetes is

high. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) defines prediabetes as either an

impaired fasting plasma glucose of 100 to 125 mg/dL or an impaired glucose

tolerance as determined by a two-hour post–glucose load plasma glucose of 140

to 199 mg/dL after taking 75 g of anhydrous glucose dissolved in water.1

Pathogenesis

The underlying pathway for

development of type 2 diabetes is unclear; however, experts postulate

abdominal obesity and insulin resistance is a main contributor.4

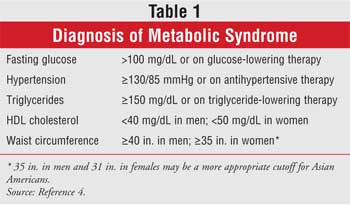

Metabolic syndrome is commonly associated with insulin resistance and

abdominal obesity and is a common risk factor for diabetes and cardiovascular

disease. There are several definitions for diagnosis of the metabolic

syndrome. The Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP III)definition is commonly used

in clinical practice due to clinical simplicity.4 It has been

modified slightly and supported by the American Heart Association and the

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. According to these criteria,

metabolic syndrome is diagnosed in individuals who meet at least three of the

criteria identified in Table 1.4

The underlying pathogenic changes that take

place predispose a patient to several metabolic alterations, including

abnormal changes to glycemia, decreased HDL cholesterol levels, increased

small dense atherogenic LDL cholesterol levels, increased triglyceride levels,

hypertension, and hypercoagulable states.4 Genetic

predisposition may have a role; however, lifestyle choices appear to have a

tremendous role in development. Metabolic syndrome is often apparent in

patients with increased weight, sedentary lifestyle, and a positive smoking

history.5

Risk Factors

While there are several

modifiable risk factors associated with diabetes, it is important to identify

those that are nonmodifiable. The development of diabetes is often linked

within families. People who have a first- or second-degree relative with

diabetes have an increased genetic predisposition for the disease. Increased

age is also associated with diabetes development. The highest incidence of

diabetes occurs in those ages 65 to 74.6 Although type 2 diabetes

was once traditionally associated with advanced age, due to changes in

American culture (including increased sedentary lifestyles and high-calorie,

high-fat diets), the incidence has risen in adolescents and younger adults.

Persons of certain ethnic origins have a disproportionately increased risk of

developing type 2 diabetes. Those considered at highest risk include Americans

of African, Asian, Latino/Hispanic, and Native American or Pacific Islander

descent1.

While some of the risk factors for diabetes

cannot be changed, there are several risk factors that can. One of the major

modifiable risk factors for the development of diabetes is obesity.4

Guidelines from the ADA recommend persons age 45 years or older be screened

for prediabetes or diabetes, especially if they are overweight.1

Younger individuals may be screened if they are overweight and have additional

risk factors.1

Obesity is often associated with a sedentary

lifestyle. The morbidity and mortality associated with obesity is concerning

considering the increase in risk of several disease states, including

hypertension, coronary heart disease, and diabetes.4,5 Overweight

(BMI = 25-30 kg/m2) and obese individuals (BMI >30 kg/m2

) have an increased risk of several disease-state risk factors. Increased

weight, especially abdominal obesity, is also associated with the metabolic

syndrome through several proposed mechanisms associated with increased adipose

tissue mass.4

Interventions

Data support that even a moderate

decrease in weight of 5% to 10% helps to improve underlying insulin resistance.

4,7-9 Risk of progression to type 2 diabetes has been observed to

decrease with decreasing weight; increasing physical activity; eating a diet

that is low in saturated and trans fat, low in cholesterol, and high in fiber;

minimizing alcohol consumption; and quitting smoking. Patients at risk for

diabetes should be encouraged to engage in at least 30 minutes of moderately

intense physical activity most days of the week.1,4

There are several studies that support

lifestyle intervention as an effective method in decreasing the risk of

diabetes. The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) Trial randomized 3,234

patients with prediabetes to receive pharmacologic or nonpharmacologic

intervention to determine if the progression to overt diabetes could be halted

in those with impaired glucose tolerance. Of the three groups included in the

study, one received metformin 850 mg twice daily with a standard regimen of

diet and exercise. Another made intensive lifestyle changes aimed at

decreasing weight by 7% utilizing a low-calorie, low-fat diet and maintaining

moderate physical activity at 150 minutes per week. The third group received

placebo tablets twice daily as well as a standard regimen of diet and exercise.

7 After an average follow-up time of 2.8 years, there was a 58% and 31%

reduction in the progression to diabetes, compared to placebo in the intensive

lifestyle modification group and metformin groups, respectively.7

The results of this study support the rationale that intensive lifestyle

changes are effective in decreasing the progression to diabetes in high-risk

patients.

Additional data from other trials, such as

the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Program, support that a relatively small

decrease in weight (in this case 5%) through lifestyle intervention still has

a significant impact in decreasing the risk of progression to diabetes.8

For patients in whom diet and exercise are not enough to decrease weight,

other weight loss options may be available. The XENical in the Prevention of

Diabetes in Obese Subjects (XENDOS) study randomized 3,305 obese individuals

to receive placebo or orlisat in addition to a low-calorie, limited-fat diet

and encouragement to participate in regular physical activity. At enrollment,

approximately 40% of individuals had impaired glucose tolerance. At the end of

the four-year study period, there was a 37.2% decrease in the incidence of

diabetes in patients with preexisting glucose intolerance who received active

drug and lifestyle modifications versus placebo and lifestyle modifications.

9 For some patients with severe obesity or who have obesity-related

complications, bariatric surgery may also be an option.10

Persons with a past history of impaired

fasting glucose or impaired glucose tolerance are also at high risk of

progression to diabetes later in life. Although it may take several years, the

predictive risk is high unless interventions are made. Included in this risk

category are women with a history of gestational diabetes, which occurs in up

to 14% of pregnancies.11 Even if normoglycemia returns postpartum,

these woman have an increased lifetime risk of future development of diabetes.

11 Women at highest risk are those who have a family history of

diabetes; are overweight or obese at the beginning of pregnancy; have

previously had impaired glucose tolerance; have had a baby weighing more than

9 lb.; or had previous glycosuria.1 Women meeting these criteria

should be screened at their first prenatal visit.1 Women with a

history of polycsytic ovary syndrome (PCOS) also have an increased risk of

impaired glucose tolerance and diabetes.12 Among other factors,

PCOS is often associated with overweight, obesity, and insulin resistance; and

although difficult, a decrease in weight will improve glycemic control.

Metformin and thiazolidenediones are also used in this patient population to

improve blood sugar and insulin sensitivity.12 Women with a lower

risk or those who test negative should be evaluated again in the 24th to 28th

week of pregnancy.1

Once an individual is considered at high

risk for the future development of diabetes, aggressive interventions are

needed to decrease the risk of progression. In addition to lifestyle

intervention, which have a primary role, there are also pharmacological

options available. As mentioned previously, metformin, as used in the DPP

study, is proven to be efficacious in individuals with prediabetes. The

STOP-NIDDM study demonstrated acarbose to be effective in individuals with

impaired glucose tolerance.13 This is a reasonable option in

patients who have postprandial elevations in glucose. Patients prescribed

these agents should be monitored to ensure safety and efficacy.

Metformin may be started at 500 or 850 mg

once daily and titrated to a maximum effective dosage of 2,550 mg daily in

divided doses.14 Gastrointestinal side effects are the most common

dose-limiting factor and may be improved with the extended-release formulation.

14 While the development of lactic acidosis is rare, it can be

life-threatening. Because of this increased risk, metformin should be used

with caution in patients with severe hepatic disease, alcoholism, previous

history of lactic acidosis, or conditions predisposing them to lactic acidosis.

14,15 An increased risk of lactic acidosis is particularly concerning in

patients with a history of renal disease who are receiving metformin. These

patients should be monitored carefully while on metformin therapy. Metformin

is contraindicated in males and females with serum creatinine levels of

greater than 1.5 mg/dL and greater than 1.4 mg/dL, respectively.15

Renal function should be monitored prior to initiation and at least annually

thereafter.15

Acarbose is often started at 25 mg right

before meals and may be slowly titrated to 100 mg three times daily.14

Dose-limiting side effects are often gastrointestinal and are a main reason

for discontinuation of the agent. Higher doses may increase serum

transaminases; these should be checked every three months for the first year,

then periodically. The dose should be decreased or discontinued if there is an

increase in transaminases. Caution should be used in patients with renal

disease. Acarbose should not be used in patients with severe liver

disease, those with inflammatory bowel disease, or patients with other chronic

intestinal conditions.16

The Role of the Pharmacist

Pharmacists are encouraged to

inform patients that although drug therapy is a viable option in prediabetic

patients, it should always be used as an adjunct to lifestyle intervention.

Pharmacists' awareness that improvement in diabetes-associated risk factors is

a multifactorial approach is vital. Most of the afore-mentioned interventions

help to decrease the risk of other conditions such as cardiovascular disease

and hypertension. Patient education is an important intervention. For some

patients, an understanding of the disease state and risk of complications is

enough incentive to be better invested in their own care. Patients should have

a clear understanding of the risk factors that predispose them to diabetes and

ithe ntervention strategies available for prevention and treatment. In order

to implement and sustain lifestyle interventions, patients may need

specialized care within a multidisciplinary team approach.

References

1. Clinical Practice

Recommendations 2007. American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care.

2007;30(suppl 1):S4-S65.

2. American Diabetes Association.

Total prevalence of diabetes & pre-diabetes. Available at:

diabetes.org/diabetes-statistics/prevalence.jsp. Accessed August 16, 2007.

3. Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention. National diabetes fact sheet: general information and national

estimates on diabetes in the United States, 2003. Rev ed. Atlanta, GA: U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention, 2004. Available at: www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/pdf/ndfs_2003.pdf.

Accessed August 16, 2007.

4. Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR,

et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart

Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute scientific statement.

Circulation. 2005;112;2735-2752.

5. Hu FB, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, et

al. Diet, lifestyle, and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in women. N

Engl J Med. 2001;345:790-797.

6. Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention. Incidence of diagnosed diabetes per 1000 population aged 18-79

years, by age, United States, 1980-2005. Available at:

www.cdc.gov/diabetes/statistics/incidence/fig3.htm. Accessed August 16, 2007.

7. Diabetes Prevention Program

Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle

intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002; 346:393-403.

8. Tuomilehto J, Lindström J,

Eriksson JG, et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in

lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med.

2001;344:1343-1350.

9. Torgerson JS, Hauptman J, Boldrin

MN, Sjöström L. XENical in the prevention of diabetes in obese subjects

(XENDOS) study: a randomized study of orlistat as an adjunct to lifestyle

changes for the prevention of type 2 diabetes in obese patients. Diabetes

Care. 2004;27:155-161.

10. Folli F, Pontiroli AE,

Schwesinger WH. Metabolic aspects of bariatric surgery. Med Clin N Am.

2007;91:393-414.

11. Jovanovic L, Pettitt DJ.

Gestational diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 2001; 286:2516-2518.

12. Ehrmann DA. Polycystic ovary

syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1223-1236.

13. Chiasson J, Josse RG, Gomis R, et

al. Acarbose treatment and the risk of cardiovascular disease and hypertension

in patients with impaired glucose tolerance: facts and interpretations

concerning the critical analysis of the STOP-NIDDM Trial data. JAMA.

2003;290:486-494.

14. Nolte MS, Karam JH. Pancreatic

hormones and antidiabetic drugs. In: Katzung BG, ed. Basic and Clinical

Pharmacology. 10th ed. New York, NY: Mc-Graw Hill; 2007:697-698.

15. Glucophage/Glucophage XR [package

insert]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2006.

16. Precose [package insert]. West

Haven, CT: Bayer Pharmaceutical Corporation; 2004.

To comment on this article, contact

editor@uspharmacist.com.